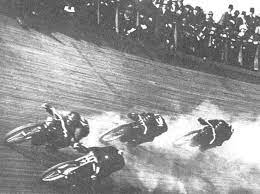

Welcome to our photo gallery section, where we invite you to take a visual journey back in time to explore the captivating history and nostalgic charm of board track racing in America. Through a collection of carefully curated photographs, we aim to transport you to the thrilling world of these wooden ovals and immerse you in the exhilarating atmosphere of this bygone era. As you browse through these captivating images, you'll witness the birth and evolution of board track racing, from its early beginnings to its heyday in the 1910s and 1920s. You'll witness the courage and determination of the pioneering riders as they fearlessly navigate the steeply banked curves and push their machines to the limits of speed. Step into the past and see the motordromes come to life before your eyes. Experience the grandeur of these magnificent tracks, stretching out like wooden arteries across the American landscape. Marvel at their impressive dimensions, with lengths often exceeding a mile, and admire the intricate craftsmanship that went into their construction. Our photo gallery introduces you to the legendary riders who became icons of the sport. See the likes of Eddie Hasha, known as the "Texas Cyclone," as he fearlessly maneuvers his motorcycle with precision and grace. Witness the intense rivalries that ignited fierce competition on the tracks, as riders like Jake DeRosier and Ray Weishaar captivated audiences with their skill and determination. Travel back in time and witness the birth of automobile racing on the board tracks. Behold the powerful machines that revolutionized the sport, with their large engines and aerodynamic designs. Explore the iconic cars driven by racing legends such as Barney Oldfield, Ralph DePalma, and Louis Chevrolet, as they made history on these wooden ovals. But board track racing wasn't just about the riders and their machines—it was also about the spectators who gathered in droves to witness these thrilling spectacles. Our photo gallery captures the energy and excitement in the air, as crowds gather in anticipation, eagerly awaiting the roar of engines and the thunderous speed that was about to unfold before their eyes. As you explore these evocative images, you'll also become aware of the risks and dangers that lurked beneath the surface of this thrilling sport. Board track racing was not without its tragedies, as accidents and fatalities became an unfortunate reality. These haunting images serve as a reminder of the sacrifices made by those who dared to push the boundaries of speed and inspire a new generation of safety measures in motorsports. Through our photo gallery, we aim to evoke a sense of nostalgia for this captivating era in American racing history. We invite you to immerse yourself in the sights and sounds of board track racing, to marvel at the courage and skill of the riders, and to appreciate the legacy they left behind. So, embark on this visual journey with us and let these photographs transport you to a time when wooden tracks echoed with the thunderous roars of engines and the cheers of passionate spectators. Explore the history, relive the excitement, and indulge in the nostalgia of board track racing in America.

Atlanta's Black Streak Racers The Other Harley-Davidson vs Indian War

credit to biker Dave and the Vintagent for uncovering this lost history that proves behind the scenes things were not heartless as you are told

A while back I heard a rumor there was a group of black board track motorcycle racers from Atlanta, GA. I checked around and found one photo from 1919, but no other information. I began contacting my board track racing sources, but no one had heard about them. One day I received package from Stephen Wright of Morro Bay, CA. with a few period articles from his collection. With those articles, I was able to put together the article below about this little-known piece of early motorcycle racing history. This article would not have been possible with Stephen Wright's assistance.

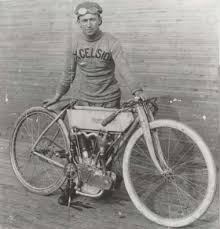

Beginning in the mid-teens, factory racing teams from both Indian and Harley-Davidson fought a hard battle for dominance on the board and dirt tracks around the country. Great riders like, Gene Walker, Shrimp Burns, Otto Walker, and many others made their names riding for either the Indian Wigwam or the Harley Wrecking Crew. The bikes they rode were little more than bicycles, with powerful V twin engines, and no brakes. Motorcycle racing was a major spectator sport and drew tens of thousands of spectators across the country.

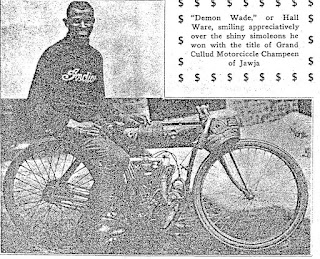

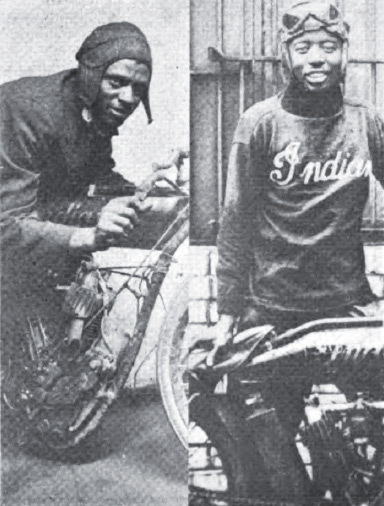

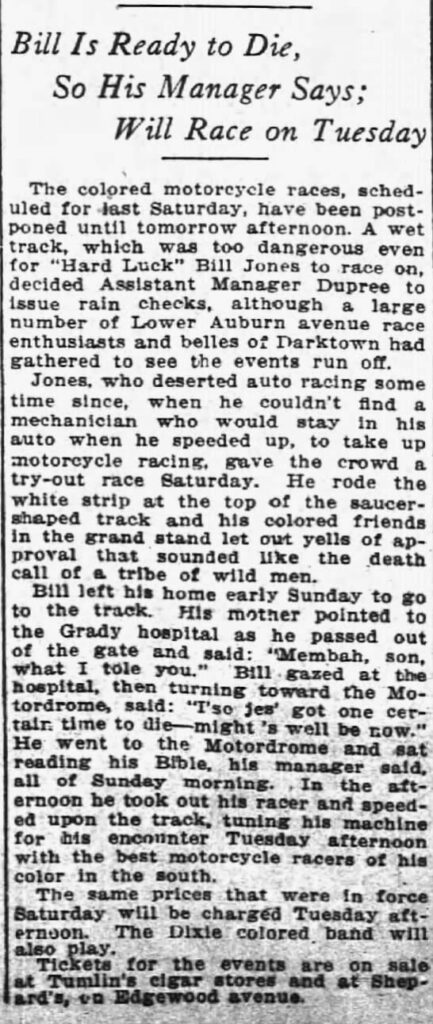

Beginning In 1913, another group of motorcycle racers sought fame and fortune on the racetracks around Atlanta, Georgia. These black riders had colorful nicknames like, "Hard Luck" Bill Jones, Hall “Demon Wade” Ware, Horace “Midnight” Blanton, and “Bones the Outlaw,” and raced each other first at the Atlanta Speedway, and later at the Motordrome board track, as well as the Lakewood Speedway. They did not have the latest factory racing bikes, and their racers were often cobbled together with obsolete parts from the scrap piles of the local motorcycle dealers. They were known as Atlanta’s ‘Black Streaks’ and while their races were covered by the national motorcycle press, the articles reflected the racial prejudice of the day, with a 1919 Motorcycling and Bicycling article titled “When Dinge Met Dinge in Georgia”; the text was even worse.

In 1909, Coca Cola founder Asa Candler opened the Atlanta Speedway in an area, which is now the site of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. The two-mile oval track featured an asphalt and gravel racing surface, which was modeled after the recently opened Indianapolis Speedway. Motorcycle races for white riders were held there beginning in November 1909. The first mention of a motorcycle race for black riders, comes in an Atlanta Constitution article on events held at the Speedway on Labor Day 1913 by the " Atlanta Colored Labor Day Association."

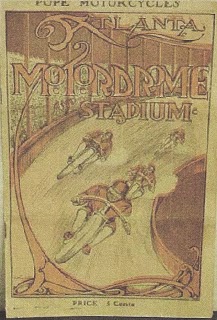

The race featured a black automobile racer, "Hard Luck" Bill Jones, who had recently switched to racing motorcycles. The only race results appeared in a later Constitution article on Jones. John Sims on an Indian was the winner. In May 1913, Jack Prince came to Atlanta to build a board track for motorcycle racing. The 1/4-mile circular track, named the Atlanta Motordrome, was built on the site of the old Fairgrounds at Jackson Street NE and Old Wheat Street close to Atlanta's Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Jack Prince Jack Prince built several of these early circular tracks, which featured a nearly vertical racing surface of rough sawn lumber. They were often referred to as "Saucer Tracks."

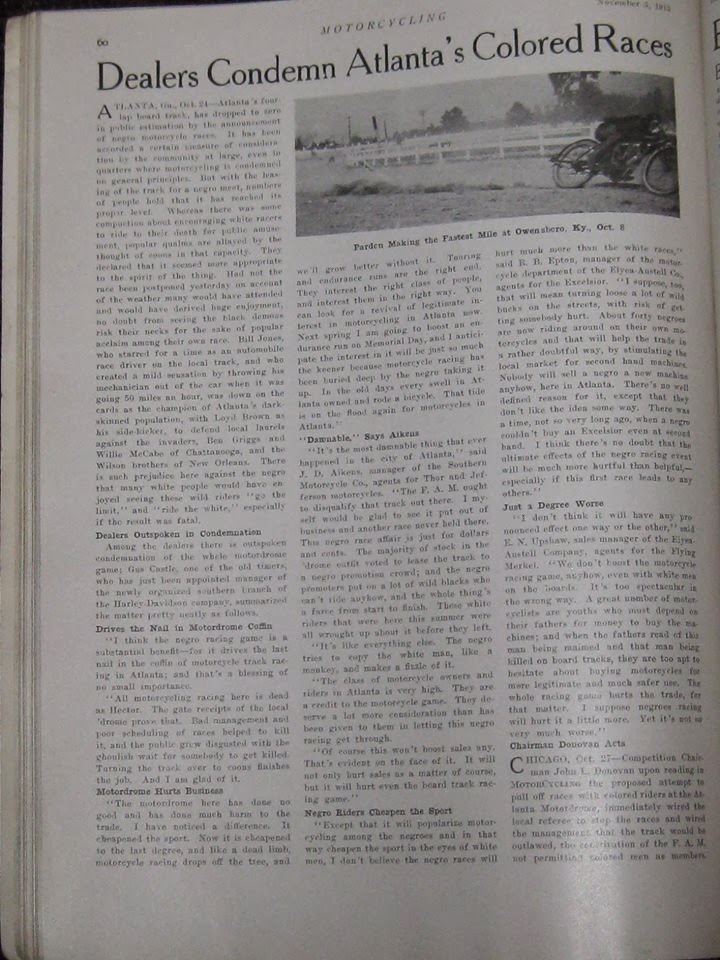

The race featuring black riders took place at the Motordrome on afternoon of October 28, 1913. The race featured black riders Bill Jones, and Lloyd Brown of Atlanta, along with the Wilson brothers from New Orleans, and Ben Griggs and Willie McCabe of Chattanooga. The Atlanta Constitution did not cover the race, and the results are unknown. Less than a month after the race, an article appeared in Motorcycling World and Bicycling Review that stated the owners of the Motordrome, had filed for bankruptcy. It further stated: “This Motordrome earned an unsavory reputation by pulling off a race with negro riders, in defiance of F.A.M. regulations, thereby becoming outlawed as long as the present management exists.” The Motordrome reopened the following year under new management. There is no record of any further races featuring black riders at the track. With the opening of the Lakewood Speedway, motorcycle racing shifted away from the Motordrome.

The one-mile dirt oval Lakewood Speedway opened south of the city in 1917 and began running motorcycle races. The track owners revived the races for black riders, which they billed as the Grand Colored Motorcycle Championship Race. " A black South Carolina racer named Tom Reese, who called himself the Champion of South Carolina, arrived in Atlanta for the June race." Reese’s manager began to brag that Reese could beat any Atlanta rider and he was prepared to place a large cash wager to back up his claim.

The event drew large crowds from Atlanta’s black community, and wagers were placed on the favorite riders. While the Harley-Davidson and Indian factories had no involvement in these races, the local white Harley-Davidson and Indian dealers gave limited assistance to their chosen racers. They also often placed large wagers between themselves on the outcome of the race.

On May 31, 1919, Bones the Outlaw appeared in a pre-race article for the 1919 Southern Dirt Track Championship, which featured top white riders from around the south, including Birmingham's Gene Walker, and Atlanta's Nemo Lancaster. Bones was standing with his employer Harry Glenn.

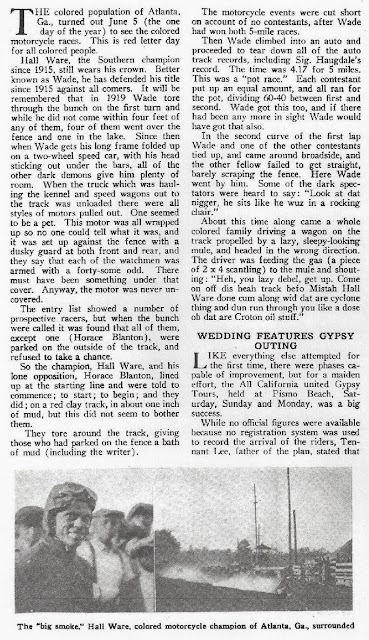

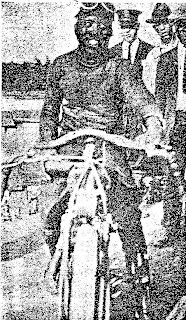

At the local Indian dealer, Hall “Demon Wade” Ware saw an opportunity. Already an accomplished local racer, Ware worked for the dealer as a mechanic. He convinced his boss, Nemo Lancaster, to lend him a competitive bike to race against Reese. While Lancaster recognized Ware’s talent, the rumor was he had a very large side bet with Reese’s manager. At the start of the race, Reese on a Harley-Davidson jumped out to an early lead. Reese’s manager was already looking forward to winning the wager. Ware, on the loaned Indian, soon caught the Carolina Champion, and passed him winning the race. Ware claimed the $150 first prize, and Lancaster collected on large side bet with Reese’s manager. The race in August 1919, was another hard-fought battle between Demon Wade, and Bones the Outlaw. Midnight Blanton won several of the preliminary races and had a shot at winning the championship race. The night before the race, Atlanta board track racer Hammond Springs (who was white) helped Wade install Springs new Indian racing engine into Wade’s older Indian frame. The competitive engine allowed Wade the edge he needed to leave Blanton in his dust. On the final lap, he and Bones the Outlaw, crossed the line in a tie. This required a rematch, which Wade won hands down, claiming the 1919 championship. The race held on June 5, 1922, proved to be a bit of a disappointment. Once again, several racers from around the south arrived, prepared to race. When Hal Wade's bike was unloaded, the motor was covered. This gave rise to rumors; Wade had another special racing engine. Wade was close to his former employer, Harry Glenn, who was now and Indian factory representative.

By the 1924 race, Bones the Outlaw switched to racing automobiles, and Demon Wade had sold his machine and moved north. For the 1924 races, Bones the Outlaw made a demonstration run in his racing car, blasting around the dirt oval and putting on quite a show, narrowly avoiding crashing several times. In the motorcycle race, Horace Blanton had no real competition, his two chief rivals having moved on, and he easily claimed the championship over a field of less experienced riders. The 1924 race appears to have been the final race for the black racers, and the story of the Atlanta Black Streak racers eventually faded into history. Still, for seven years a group of black motorcycle created a unique story in the Jim Crow south and had their moment in the limelight. Author's Note: This 1919 Motorcycling and Bicycling Magazine article about Atlanta's Black Streak Racers uses language that reflects the racist attitudes of the time. It is included for historical context, and to show the prejudice these young men endured during their racing careers.

Horace "Midnight" Blanton 1924 Champion

Our vision at HARKEN-CYCLES is to preserve the legacy of early 20th-century motorcycles by replicating their iconic designs and craftsmanship. We aim to provide enthusiasts with a starting with our entry level kits which serve as a blank canvas for you to create your dream bike, combining the nostalgia of the past with the innovation of electric/gas motorized bikes. Through our dedication to quality and attention to detail, we strive to become the leading provider of entry level antique motorcycle replicas/tributes and contribute to the continued appreciation of these timeless machines

Let’s talk.

harkenville@duck.com